A Quick-Dive into the Adverse Effects

The foggy air of cannabis debates is clearing to reveal a stark reality—its use, especially among college students, has far-reaching implications that extend beyond the hazy highs to affect psychosocial facets. Recent studies have shone a spotlight on the link between college students’ cannabis use and a buffet of adverse outcomes including depression, anxiety, and even violent victimization. This delicate subtext unearthed from the bustling collegiate environment demands a re-evaluation of institutional strategies and a more informed conversation about drug education and support systems.

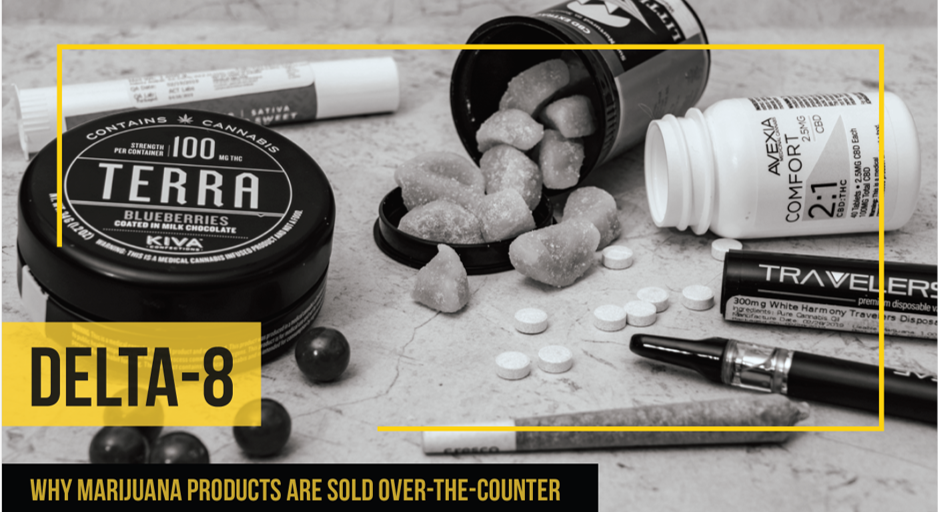

Navigating the Statistics on College Cannabis Use

Cannabis, among college students, has transcended the ‘rite of passage’ narrative to burgeon into a widespread truth. The numbers don’t lie – approximately 20% of North American college students confessed to using cannabis within the past 30 days. This staggering statistic isn’t just about recreational choices; it’s an indicator of a deeper, more complex situation that warrants vigilance and constructive intervention strategies.

But what exactly do these usage statistics mean in the grander scheme of college life? The implications are diverse and profound. They echo in the corridors of academic institutions and affect a plethora of experiences, from mental health to social engagements.

The Psychosocial Trail of Cannabis in College

The correlation between cannabis use and psychosocial elements paints a picture of alarm. A study spanning across thousands of students revealed that cannabis users were at significantly higher odds of experiencing depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, anxiety, eating disorders, and victimization. These findings are a call to action for universities, highlighting the need for expanded educational programs, evidence-based prevention strategies, and intensified early-intervention tactics.

Cannabis users in college also reported a greater prevalence of co-use with other substances, indicating a possible trend of polydrug engagement. This alarmingly intertwines with patterns of daily stress, drinking motives, and beyond. The clear narrative emerging is that cannabis, when entangled with social and academic pressures, can become a combustible mix leading to multifaceted detriments.

Crafting Collegiate Responses to Cannabis Use

In the wake of these revelations, academic institutions are implored to revisit their support frameworks for students. Strategies that aim to redefine the cannabis conversation and offer multilayered assistance have never been more pivotal.

Colleges should consider implementing stringent policies that address substance abuse within the student community while avoiding the stigmatization of users. Initiatives focusing on stress management, mental wellness, and peer support can serve as preventive measures, intervening before cannabis use spirals into adverse psychosocial implications.

Additionally, robust support systems that offer counseling, personalized interventions, and harm-reduction models can be invaluable in reaching out to students who’ve already taken the cannabis plunge. Such systems should work in tandem with educational campaigns that emphasize the long-term effects of cannabis on the young, developing mind.

The Neurological Pathways of Cannabis

To truly understand the impact of cannabis on college students’ psychosocial health, it’s indispensable to explore the neurological implications. The brain undergoes significant changes during adolescence and young adulthood, making this a particularly vulnerable period. Cannabis use can interfere with the maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for complex cognitive behavior, decision making, and the moderation of social behavior.

Further, the endocannabinoid system, which cannabis influences, plays a pivotal role in memory, reward processing, and stress responses. Disruption to this system can have profound effects on these domains. For college students on the cusp of adulthood, where cognitive and emotional growth are in flux, the implications of cannabis reach beyond just the act of consumption.

A Multidisciplinary Approach to Tackling College Cannabis Use

Efforts to minimize cannabis-associated health risks among college students require a multidisciplinary approach. This approach should combine the expertise of educators, mental health professionals, and addiction specialists. By fostering dialogue, imparting robust educational programs, and developing interventions that cater to individual needs, we can guide students towards healthier choices.

Redefining Prevention in the College Context

When addressing cannabis use, prevention is key. However, traditional drug prevention models can be outdated and ineffective at the college level. It’s time to embody a dynamic, progressive prevention ethos that resonates with the modern college student.

This ethos starts with understanding the student body’s motivations, triggers, and environmental stressors. By creating tailored educational initiatives and fostering a culture of health and resilience, colleges can play a significant role in prevention efforts.

Leveraging Technology and Student Engagement

In the digital age, technology can be a powerful ally in the battle against cannabis misuse. Platforms that offer anonymous support, data-driven feedback on usage patterns, and curated content centered on harm-reduction principles can foster engagement and provoke thought. Gamified interventions and peer-led support networks can also provide a supplementary layer of reach and relatability that traditional methods may lack.

Integrating Cannabis Education into the Curriculum

While cannabis education often falls under the purview of student services or public health initiatives, there is merit in integrating it into the academic curriculum. By incorporating cannabis studies into relevant disciplines like psychology, sociology, and public health, colleges can present a nuanced view of the drug and its implications. This would not only create a more informed student body but could also foster research that informs future policy and interventions.

Conclusion

Cannabis use is a nuanced issue, particularly among college students. It encompasses a spectrum of experiences, motivations, and consequences that challenge conventional paradigms. In the face of mounting evidence, it’s the responsibility of college administrations to evolve their strategies, policies, and support systems to address the complex interplay between cannabis and the college experience.

The path forward lies in a commitment to comprehensive research, empathetic understanding, and the development of innovative, student-centered solutions. By leading the conversation with knowledge and proactive approaches, colleges can help shape a safer and more fulfilling educational environment for all their students.

References

1.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10826084.2024.2320374

2.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10826084.2023.2247075?journalCode=isum20